Note from Lois:

Usually, my blogs describe the joy of the Great Outdoors, whether sailing, traveling, gardening or just enjoying nature. But sometimes a traveler falls in love with a destination, only to see it degenerate year after year. This story looks into the pain of seeing a UNESCO World Heritage city destroyed before our very eyes.

My heart bleeds for Yemen. For centuries, this country was reportedly the least known in Arabia. As I posted in another blog, Yemen—Al Qaeda, Qat Chewing, and So Much More, “King Solomon knew of this legendary land long before the Queen of Sheba visited his court with her gorgeous gifts. Yemen, along with Oman, is known for its rich resources of frankincense, spice, and myrrh. Great empires emerged there centuries before Christ. Here, the Biblical Noah launched his famous ark. Yemen was called The Pearl of the Peninsula.”

What happened? First, most of Yemen’s adult population chews an intoxicating leaf called Qat. Imagine a western country where most everyone smokes marijuana from noon until bedtime! Chewing qat is a way of life in Yemen. Growing qat requires an abundance of water, and when we sailed there in 2004 during our world circumnavigation, Yemen was already running out of water. Second, the economy was cratering. And third, three-fourths of the population was under 25 and jobs were scarce. The country was ripe for takeover.

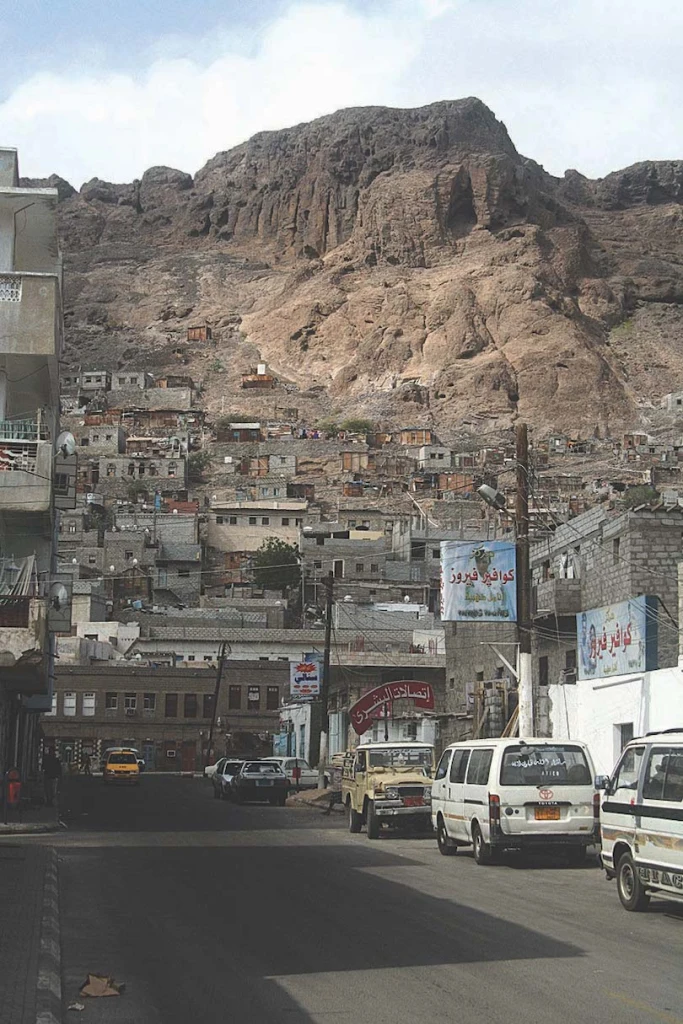

From Aden to Sana’a. Gunter and I saw signs of impending problems during our visit. We had sailed safely from Oman through Pirate Alley to the harbor in Aden, Yemen (yes, that place where Al Qaeda bombed the U.S.S Cole). We performed the usual maintenance of our catamaran Pacific Bliss and then decided to travel to the capital city, Sana’a, in the interior. Old Sana’a is a UNESCO heritage site, and at that time, was the best preserved in the whole of the Arab world.

The crews of Winpocke and Legend and another cruiser, Dietrich, along with our crew, Chris, piled into a dilapidated van. Our driver took us to a rundown building in Aden where we picked up tourist permits (ten copies each). Soon we passed through the outskirts of Aden and into a bleak countryside with struggling trees, gray boulders, and acres of brown sand. Grass huts appeared here and there. Within an hour, we were at our first of ten checkpoints. I asked the driver, “Why do they track us so carefully?”

“For your protection,” he answered. “Kidnappings. If one of you should disappear, the government would be able to track where you were from the last checkpoint.” (A week later, I read a story in the Yemen Times: A group of tourists brought to Marib, Yemen’s oldest city, by a Bedouin guide, was captured and held for ransom by Al Qaeda. Apparently, their guide had been paid to lead them to the Queen of Sheba Temple and the great Marib dam.)

We drove farther into the countryside. The flat land yielded to rolling hills. We bumped along the dusty road passing rocky outcrops, scrub, and an occasional mudbrick hovel. These people were poor, dirt poor, and I wondered how they could afford a vice like qat. We stopped for lunch in a small town. Curious children crowded around us as our driver parked the van. Our group entered the town’s sole restaurant housed in a decrepit two-story building made of unpainted wood and corrugated iron. The lunch special was chicken floating in a greasy sauce in a dented pan atop a rusty burner. I knew I wouldn’t order that!

We pulled up stools and scooted around a dirty, unpainted wooden table. Along with an obligatory, framed picture of then-President Saleh, a few torn posters of Saddam Hussein decorated the plasterboard walls. The proprietor pulled our driver aside. “There isn’t enough chicken for a group of nine.”

Just as well. Part of our group had already started to leave after taking a closer look around. We bought fruit that we could peel, such as bananas, and piled back into the van. As we continued to drive north, pink plastic bags blown from the market lined the hilly desert landscape for miles. They caught on dry shrubs and puffed in the wind like limp balloons.

“The National Flower of Yemen,” I joked. But as we drove on through one small town after another, the immense trash problem was no laughing matter. Piles of garbage were everywhere. Apparently, whenever anyone consumed a drink from a can or bottle, he or she simply dropped it.

Near Sana’a, rocky hills gave way to a fertile valley with terraced hills of luscious, green plants receding into the horizon.

“Qat plantations,” our driver stated. He pointed out the armed guards protecting well-maintained fields. The mud-brick houses nestled among the green were a remarkable improvement over the single-story hovels we passed along the way.

“There must be a lot of money in growing qat,” I said. He nodded vigorously.

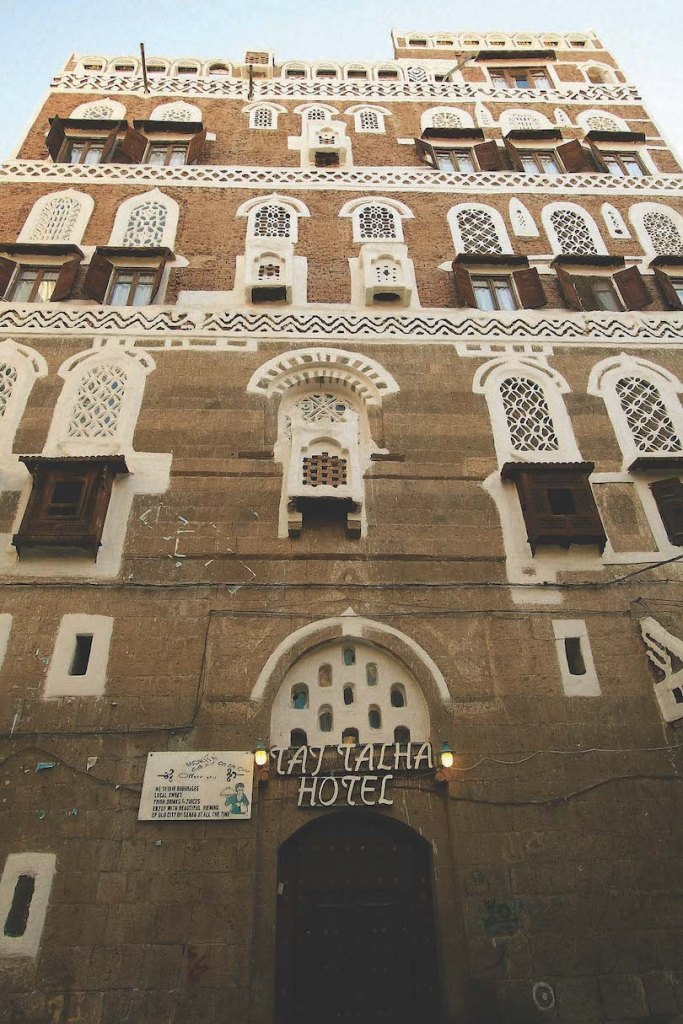

Sana’a, Yemen in 2004. On my first morning in Sana’a, I awakened to a cacophony of muezzins chanting from hundreds of minarets filling the Old City. The sounds melded together as if in deliberate harmony. Dawn’s light spread through the small stained-glass windows of our centuries-old hotel room, causing a rainbow of colors to dance on the soft white plaster of the of the ancient mud-brick walls. Quickly, I dashed in and out of the cool shower, applied my make-up in front of the lone mirror, and threw on a skirt (below my knees) a blouse (not too revealing) and a lightweight shawl that could double as a headscarf.

I groped my way down the dim spiral staircase to the small reception area and nodded to the proprietor. Walking along the sidewalk, I photographed golden shafts of light that wove through a row of sand-colored six-story buildings. Called tower homes, they’re the world’s first skyscrapers. Sana’a had 14,000 of them. Their architectural style precedes the seventh-century advent of Islam; the lower levels might date back as far as 1200 BC. Everything necessary for reconstruction when top levels tumble—mud, straw, clay and limestone—is found right outside the city gates. Construction methods haven’t changed in 4,000 years.

According to the Yemenis, the city of Sana’a is one of the first sites of human settlements, founded by Noah’s son Shem. Until 962 AD the entire city nestled between the walls of the Old City. By the time we were there in 2004, however, the population of one million had expanded to new parts of the high plateau. As I walked along, I thought about how privileged I was to be there in a country that some travel sites listed as appropriate only for “dark tourism.” Little did I know then what would happen to Old Sana’a, a UNESCO World Heritage Site I had begun to love.

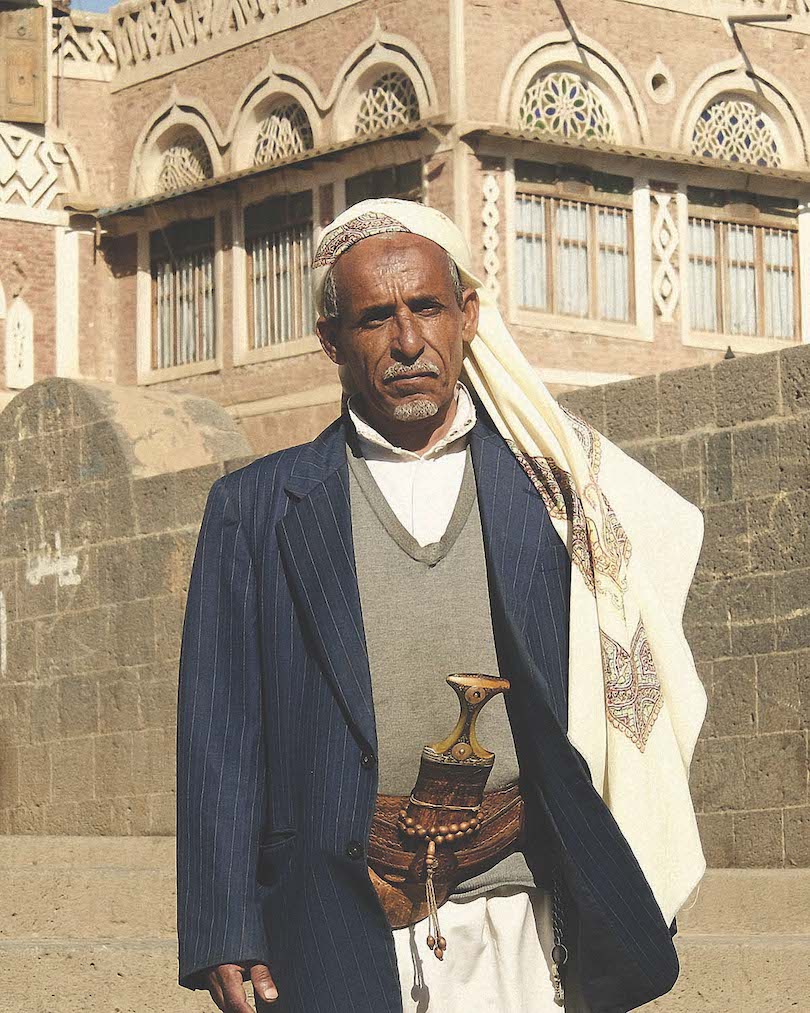

As I walked past hammams (bath houses) built during the occupation by Ottomans in the 1800s, I nodded to a trio of women clothed in black from head to toe. They furtively glanced downward, avoiding eye contact. The heavy black of their clothes against these ancient golden walls drew a dark contrast. The scene seemed lost in time. It was the first setting I’d found in which the dark Arabian abaya seemed to fit. I sensed that the women wouldn’t pose for me, but farther on, away from the shadows of the tower homes, I met Yemeni men wearing traditional dress topped with beautifully carved belts and daggers. They posed willingly, proud to have their pictures taken. As I returned to our hotel for breakfast, wide-eyed children followed me through the narrow streets, motioning that they too wanted me to take their pictures.

After siestas, when the sun is low on the horizon, the souks open. Our second day in Sana’a, Gunter was on a mission. He wanted to buy a traditional belt and dagger. I tagged along while he shopped, haggled, and shopped some more. Finally, he found a carved, beaded belt of fine leather with a matching dagger scabbard. “Does the dagger come with it?” he asked.

“Of course,” the black-bearded vendor said laconically, his right cheek bulging with qat. He took out the dagger and ran his finger carefully along the finely-honed edge. “Why would you want such a fine holster without a sharp dagger to match?”

I turned to Gunter and whispered, “Customs?” He heard me but bought the set anyway. That dagger is now displayed on a wall near the door to my office.

One evening, there was a party going on in Sana’a, with lively music and dancing in the streets near the souk. With my camera around my neck, I pushed through the crowd. A group of white-robed men opened a path for me toward a circle of men holding hands and dancing. One man pointed and motioned for me to take a photo.

“What’s the occasion?” I asked.

“Wedding celebration,” he answered.

Noticing that the entire group was composed of men, I asked, “Where’s the bride?”

“At home, celebrating with the women.”

I felt honored and surprised that these men would invite a woman into their circle, but after taking photos, I felt uncomfortable and returned to Gunter.

On our last day, we caught a cab to the new part of Sana’a that is home to the presidential palace, the parliament, the supreme court, and the country’s ministries. We passed an assortment of modern shopping centers and hotels. It was not as impressive as Old Sana’a. We told the driver about the men dancing in the souk before a wedding. “There are many weddings in March,” he said. “I can take you to a wonderful tower home where there’s a wedding today.” The taxi stopped at an incredible estate on high, rocky promontory outside of the city. Men were dancing outside on a shaded patio while the women remained inside. As I took the photo of the home carved into stone, I spied a lone woman in black. Intrigued, I included her in the photo below.

Yemen Today. Every time I hear more devastating news about Yemen I cringe and cry. In March, it will have been twenty years since we visited Yemen. The boys and girls we talked with are now in their late twenties and early thirties. Many of the boys are probably in the military, serving the Houthis who now run Sana’a. Many of the girls most likely have children of their own, some of them malnourished and ill. Others will be among the dead.

With about three-fourths of its population living in poverty, Yemen has long been the world’s poorest country; its humanitarian crisis has been called one of the worst in the world. Disease runs rampart; suspected cholera cases passed 200,000 in 2020. And that was before Covid swept through the country! Sadly, many countries cut critical aid during the pandemic, leading UN organizations to reduce food rations for some eight million Yemenis in 2022. Three out of four Yeminis now require humanitarian aid and protection; four million are internally displaced refugees.

President Ali Abduallah Saleh, whose portrait was hung in every business we visited, held power for 33 years, ruling from Sana’a from 1978-2012 when he formally handed over the reins to his deputy, Abdurabu Mansur Haidi. Back in 1993, Yemen became the first country in the Arabian Peninsula to hold multi-party elections under universal suffrage. Fifty women competed and two won seats. But as in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 lit a powder keg of longstanding dissatisfaction with dictators. Saleh was known by many as “Yemen’s godfather,” but by others as its authoritarian leader. After surviving an assassination attempt, he fled the country with immunity from prosecution. Unfortunately, the popular uprisings allowed room for competing factions to vie for power. Iran backed Shiite rebels in the Northwest and West and began a proxy war against Yemeni’s Sunni-majority government headed by Haidi. Saudi Arabia backed Yemini’s government, pushed to the south by the rebels when the Houthis took over Sana’a.

The situation changed after US President Obama sent a “planeload of cash” in various currencies (estimated at $400 million) to Iran as the first installment on a $1.7 billion settlement, part of the Iran nuclear deal signed July 14, 2015. Unfrozen assets have totaled $29-150 billion (depending on the source). Soon after, checkpoints that we cruisers went through heading north from Aden sported Death to Israel, Death to America signs. Tourism went out the window. The bloody conflict some call a “Civil War,” has continued to this day—except for a brief April 2022 ceasefire. The UN Development Program estimates that more than 370,000 people have died as a result of the war; lack of food, water, and health services represent almost 60 percent of those deaths.

Sana’a Today. Since the military campaign began in March 2015, several airstrikes have battered Old Sana’a. “Because the city’s houses are made from clay, the bombing has affected them very heavily. We have seen several UNESCO-listed houses among the damaged places,” says Mohammed al-Hakimi, an environment journalist and editor of Holm Akhdar website. “In June 2015, heavy bombing targeted Miqshamat al-Qasimi, a famous urban garden and one of the most beautiful areas in the city. In addition, airstrikes on the Ministry of Defense and National Security buildings have significantly damaged several areas given the buildings’ proximity to the old city.”

Yet even before the current conflict began, successive governments turned a blind eye to the catastrophe right in front of them. According to locals, no building maintenance had been done since 2004, when Sana’a was announced as the Capital of Arabic Culture. Even then, restoration work was confined to the outward-facing parts of the city. When the Houthis took over Sana’a in September 2014, the situation only got worse—indifference turned into desecration. The Houthis began covering many of the ancient buildings with propaganda slogans and chants.

Additionally, the sprawl of modern-style construction invaded the old city. Homeowners sold these ancient homes to developers who turned them into commercial centers. Of course, a law prohibits people to build new structures in Old Sana’a, but reportedly, bribery is endemic. Exacerbating the problem are certain Houthi policies. For example, some owners of traditional cafes and motels inside the old city have had to shut their doors because the Houthis—from a religious standpoint—have prohibited the mixing of unrelated men and women in public spaces like cafes and restaurants.

Most of the country’s problems are man-made. Ongoing neglect threatens the historic city of Sana’a, and without that history, Yemen will lose its national identity. Fortifying Old Sana’a and restoring its unparalleled beauty—in a well-managed, coordinated manner—will require a responsible government in this war-torn country. When the conflict finally comes to an end, I fear that Yemen will have nothing left to offer its people and the world.

For more on Yemen’s history, the Houthi’s involvement in Israel/Gaza war, and their targeting of international vessels passing through Bab al-Mandab, a chokepoint for international trade, watch for Part II of Yemen Then and Now.

Sources:

About the Author: Lois and Günter Hofmann lived their dream by having a 43-foot ocean-going catamaran built for them in the south of France and sailing around the world. Learn more about their travel adventures by reading Lois’s award winning nautical adventure trilogy. Read more about Lois and her adventures at her website and stay in touch with Lois by liking her Facebook page.