You may have wondered why acorns in Northwest Wisconsin seem be everywhere this year—filling yards and woods and scattering over sidewalks, driveways and roads. 2023 is experiencing a “masting year,” an outsized crop of acorns. It’s not just one oak here and there, but nearly all the oaks in a region that produce an extraordinary number of acorns in the same year. Yes, we’ve had a drought this year, but that’s not the reason, and please, don’t attribute masting to climate change. This phenomenon has begged explanation for centuries! I call it one of nature’s miracles.

The Advantage of Masting. We do know that making acorns requires lots of energy, so during mast years, oaks grow very little. This can be verified, after the fact, by examining oak growth rings. In a typical year, an oak tree can produce more than 2,000 acorns. During a mast year, that number can jump to 10,000. Mast years do not occur two years in a row. They typically occur every 5-8 years. We now know that trees communicate via an underground network of fungi. I imagine them talking to one another last year about the advantage of masting:

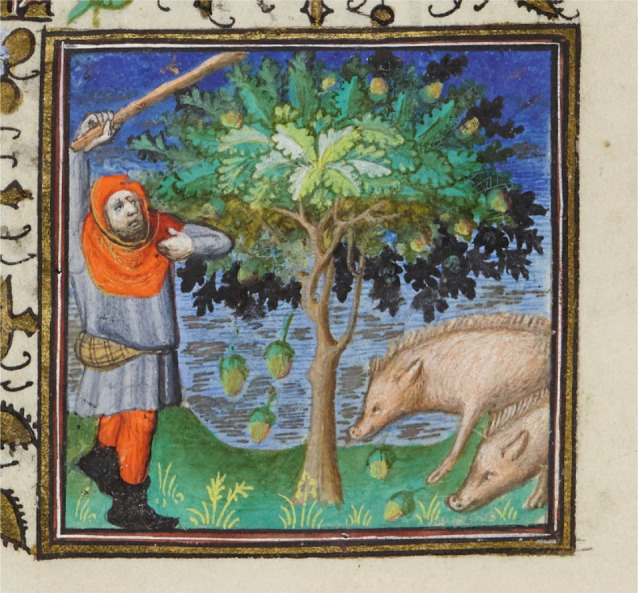

Red Oak proposes a plan to a group of oaks attending the annual Polk County Oak Society (PCOS): “Let’s make 2023 a masting year. It’s time we outwit those squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, opossums, raccoons, mice and voles. And especially those white-tailed deer who feast on our acorns—accounting for 75% of their fall diet.”

“Don’t forget the black bears,” White Oak adds. “Their population is increasing in Wisconsin. In 2022, their census count was 24,000.”

“Well, you can’t blame these predators,” Red Oak counters. “Our acorns here are the best. They contain huge amounts of nutrients. If it hadn’t been for our acorns, many of those predators would have died when the Eastern Chestnut disappeared from the forests.”

“Listen, friends,” says Bur Oak. “If all of our offspring are sacrificed, we don’t reproduce. Even though it costs us some growth, we need to flood the market with acorns again. Just for one year. At least, some acorns will escape the predatory scramble and germinate. Then we’ll have a baby boom like you wouldn’t believe!”

The vote was unanimous. 2023 will be a mast year.

The Science of Masting. Acorns provide an amazing array of nutrients: protein, carbs, and fats—as well as calcium, phosphorous, potassium and niacin. During mast years, there is unlimited food for acorn predators. This removes one of the biggest factors for population growth so birds, squirrels, mice, deer, etc. make more babies. The following year, though, a smaller crop of acorn causes the death of many of those predators. This boom-and-bust cycle keeps acorn predators low.

Masting may also improve pollination. Oaks are wind-pollinated, and (not surprisingly), wind-pollinated plants are at the mercy of the wind. Statistics tell us that pollination success will increase if there is more pollen blowing around when the female oak flowers are mature and open. Synchronizing the release of pollen in some years would result in lots of pollen, and therefore, increased pollination.

Yet another hypothesis about oak masting has to do with energy allocation. In most years, there are not enough resources such as water, nutrients, and sunlight to provide sufficient energy to grow and to make a lot of acorns at the same time. Scientists speculate that oaks partition available energy; some years they allocate it to growth; other years they direct energy to reproduction.

The Meteorology of Masting. Tune into your local radio station during a masting year and you’ll hear plenty of explanations. WXPR, “Mirror of the Northwoods, Window on the World” tells the story this way:

The plentiful supply of acorns we’re seeing now has a lot to do with the weather we experienced last fall and spring.

“It probably had favorable [precipitation] last fall. Then we didn’t have a frost that affects the germination of the flowers that actually produce the acorn,” says Doug Sippl, Forest Silviculturist for the Chequamegon Nicolet National Forest.

“There are a lot of other factors that can go into it as well. Things like the amount of sunlight an oak tree gets, the age of the tree, or how healthy it is. That’s why some parts of the Northwoods may see a mast year for acorns while other parts don’t.”

If you have oaks near where you live, you can decide for yourself which explanation makes the most sense. Enjoy watching the wildlife activity around those oaks the next time they mast. I urge you to partake of Nature’s Miracle. You could meditate under an oak tree while acorns drop on your head and chipmunks stuff their cheeks. Or you could busy yourself making acorn flour!

For further reading, I recommend The Nature of Oaks, by Douglas W. Tallamy and The Hidden Language of Trees by Peter Wohlleben.

About the Author: Lois and Günter Hofmann lived their dream by having a 43-foot ocean-going catamaran built for them in the south of France and sailing around the world. Learn more about their travel adventures by reading Lois’s award-winning nautical adventure trilogy. Read more about Lois and her adventures at her website and stay in touch with Lois by liking her Facebook page. Lois’s books can be purchased from PIP Productions on Amazon and on her website.